The microscopic anatomy of lactating breasts is highly variable (within system constraints)

Teaching the functional anatomy of the lactating breast through a complexity science lens

The mammary gland is a marvellously unique endocrine organ, because its cells have the innate capacity to diversify through cycles of growth, function, and regression multiple times in an adult female human's life - unlike most human glands, where cells differentiate into specific functionality early on in embryonic development, and remain consistently active after birth.

Often, the anatomy and function of the lactating breast is taught through a mechanistic lens. By that, I mean through the lens of the mechanistic sciences that still dominate in health, and which tend to focus on cause and effect, linearity, and machine-like analogies. However, in NDC we focus on

-

Anatomic diversity (contained within overall systems constraints), which is a natural part of the complexification forces at work in evolution

-

Functional flexibility (again contained within overall systems constraints), which challenges machine-like metaphors.

This matters, because a focus on science-based anatomic diversity and functional flexibility helps protect against unnecessary pathologisation and overtreatments.

Glandular tissue and the lactating breast

-

65% of glandular tissue is in a 30 mm radius from nipple base

-

The proportion of lobules in a lactating woman's mammary glandular tissue which are highly productive varies from 25% to 100%.

-

The amount of glandular tissue or number of ducts found in women who are exclusively and successfully breastfeeding doesn't relate to milk production and milk storage capacity.

-

A woman's two breasts usually have symmetrical proportions of glandular and fatty tissue, even though breasts are often asymmetrical in size in the one woman.

-

There is on average about twice as much glandular tissue as fatty tissue in a lactating breast. But this proportion varies a lot. Some lactating breasts are over 80% glandular tissue, other normal lactating breasts contain just 45% glandular tissue. There is no relationship discovered to date between the amount of glandular tissue and milk production.

Lactiferous ducts and the lactating breast

-

Duct width imaged by ultrasound varies between 0.1 mm and 10 mm diameters at rest. Ducts much finer than this are visualised histologically. Nevertheless, there is a 100-fold difference in ductal widths which are able to be measured in ultrasound imaging of the lactating breast.

-

Main milk ducts increase in size by a highly variable amount ranging from 0.5 - 1.9 mm with ejection reflex.

-

Main milk ducts have a greater increase in duct diameter (by almost twice as much - 76% c.f. 40 %) when the first breast is offered compared to when the second breast is offered

-

Main milk ducts run close to the outer surface of the areola. They can lie anywhere between 0.7 to 7.9 mm deep under the skin surface. This means that the ducts are compressed with even very light touch, in the same way that touch easily compresses the veins on the back of the hand.

Lack of subcutaneous fat

There is no subcutaneous fat under the nipple and areola. he ducts are exposed without a fatty padding to any vacuum effects, which helps with milk transfer. However, any prolonged superficial pressure and compression could also cause the ducts to compress shut, resulting in milk back-up, risking mastitis.

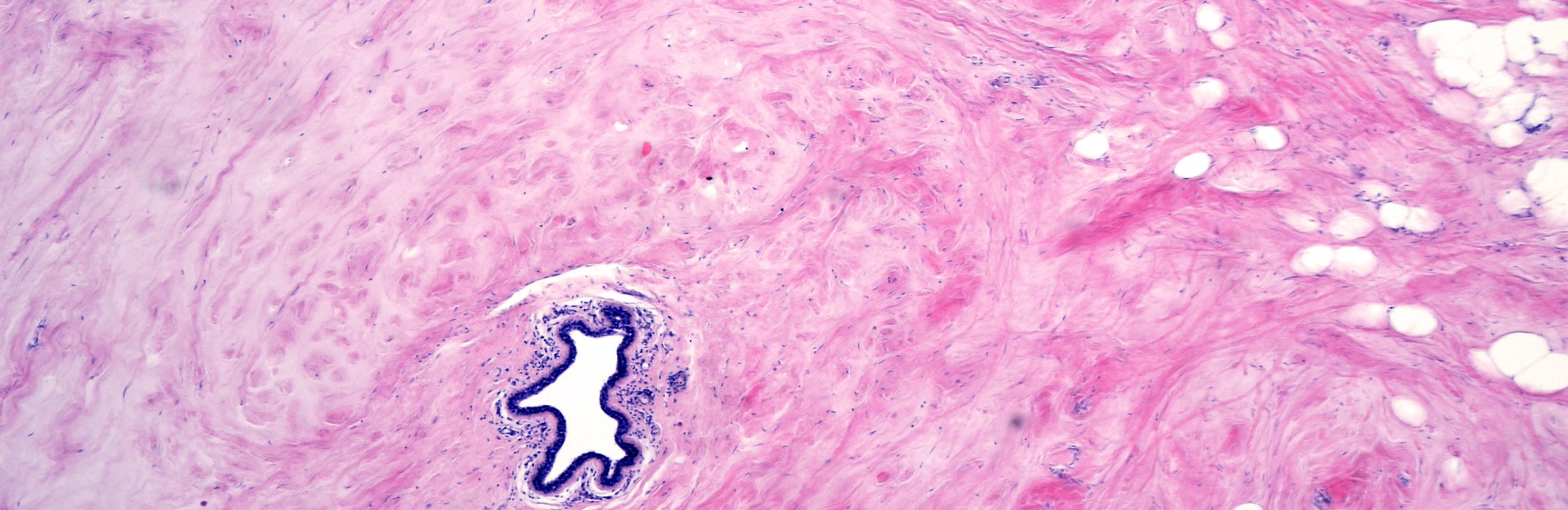

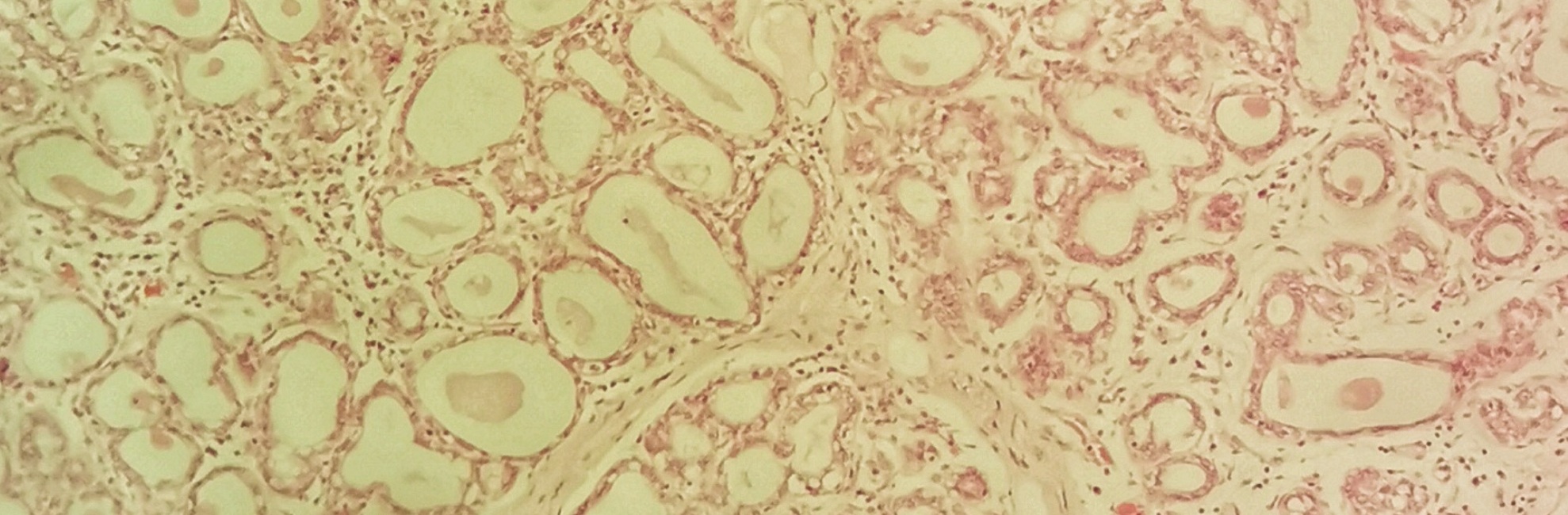

In the histological sample at the top of this page, you can see the band-like lacteriferous ducts running like an upside-down U at the bottom. You can also see many distended alveoli with stretched, rectangular lactocytes lining at them at the edges of the lumens.

Selected references

Geddes DT. The use of ultrasound to identify milk ejection in women - tips and pitfalls. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2009;4(5):doi:10.1186/1746-4385-1184-1185.

Hassiotou F, Geddes DT. Anatomy of the human mammary gland: current status of knowledge. Clinical Anatomy. 2013;26:29-48.

Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, Hartmann PE. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of Anatomy. 2005;206:525-534.

Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Ultrasound imaging of milk ejection in the breast of lactating women. Pediatics. 2004;113:361-367.

Ramsay DT, Mitoulas LR, Kent JC, Cregan M. Milk flow rates can be used to identify and investigate milk ejection in women expressing breast milk using an electric pump. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2006;1(1):14-23.